Guest

Post by Clayborn Benson III

African Americans have

played a part in Wisconsin’s history since the very beginning of the state’s

history, working as trappers, guides, and frontiersmen. They roamed the

territory with Pere Marquette; they had strange names like Black Bart, James

Pierson Beckwourth, Claude and Mary Ann Gagnier, Toby Dodge, and the Bonga

Family (Pierre, Joas, Marie Jeanne, and George). They

roamed from Green Bay to Prairie du Chien. They harvested the lumber from

Superior, WI and traded with the native Indians in Peshtigo County. The numbers

of African American citizens were never significant enough to outpopulate

anyone; however, they influenced almost every political decision made in the

state. African Americans were encouraged and invited to relocate to places like

Freedom, WI, (north of Appleton) named in honor of an African American, James

Andrew Jackson, WI. They settled in all kinds of places you would never

imagine, and they were a big support to the European citizens. They spoke many

European languages and even influenced the architectural design of the round

barns, although their population was still less than one percent.

In 1846, when

Wisconsin made the decision to become a state, the founders included in the

constitution that African American men should have the right to vote, as any

other citizen. Not only were there fierce debates in the state legislature over

African American suffrage in 1846, they were even referenced as the “N” word in

the state legislature, when their numbers in no way represented a serious

threat to the percentage of the state’s population. “Free

and unequal” is a descriptive term to describe my view of how African Americans

have been treated, particularly in Wisconsin. There are three major things that

African Americans have had to fight for throughout our presence in Wisconsin,

1) education 2) fair and decent housing, and 3) the right to vote. For the

purposes of this paper, I will focus on suffrage or the right to vote.

In 1846, when

Wisconsin made the decision to become a state, the founders included in the

constitution that African American men should have the right to vote, as any

other citizen. Not only were there fierce debates in the state legislature over

African American suffrage in 1846, they were even referenced as the “N” word in

the state legislature, when their numbers in no way represented a serious

threat to the percentage of the state’s population. “Free

and unequal” is a descriptive term to describe my view of how African Americans

have been treated, particularly in Wisconsin. There are three major things that

African Americans have had to fight for throughout our presence in Wisconsin,

1) education 2) fair and decent housing, and 3) the right to vote. For the

purposes of this paper, I will focus on suffrage or the right to vote.

According to Michael

J. McManus, PhD, “Disfranchisement implied that blacks not only were

undesirable members of their communities but were incapable of exercising the

rights and responsibilities of citizenship. In addition, the attitudes that

deprived blacks of the right to vote in the North mirrored those same

principles that in the South reduced them to servitude.”

We don’t have to go

back very far to see the current and blatant voter suppression tactics used in

Wisconsin. In April 2020, during the mayoral election in Milwaukee, only five

voting places were made available for the 31st largest city in the United

States. On

a cold, damp spring day, during the coronavirus pandemic, people stood in line

for hours waiting for the opportunity to exercise their right to vote. In

addition, African American men and women who have violated state laws,

resulting in jail time, also lose their right to vote. This is just one more

way that African Americans are disenfranchised.

In 1846 the founding

fathers put in Wisconsin’s constitution that all men should have the right to

vote. White citizens in the western part of the state, where slavery existed,

voted against African American men having the right to vote.

Statehood election

took place in 1848, but African Americans were not permitted to vote. The

state’s founders realized that giving the right to vote to African Americans

was something they wanted to do, so they called for the first of two

referendums asking for African Americans to have the right to vote—one in 1849

and another in 1857.

In 1854, Joshua Glover, a

fugitive slave from St. Louis, was arrested and broken out of jail at Cathedral

Square in Milwaukee. This was in direct conflict with the Fugitive Slave Law

passed by U.S. Congress just four years earlier. Wisconsin was one of the only

states in the Union to openly defy the Fugitive Slave Law. The thing that makes

this unique and special is that the governor and abolitionists all believed that

defying federal law was the right thing to do. Wisconsin’s Governor Alexander

Williams Randall asked that the local militia stand ready to protect the state;

because of their actions President Buchanan was threatening the state for

violating the Constitution. How

did the more than 99.9 percent white citizens justify taking an abolitionist’s

position of breaking a slave out of jail yet continue to disenfranchise African

Americans by refusing to allow them the right to vote?

There are conflicts between the Irish community, lynchings, and conferences on the issue of voting

rights. The 1850s brought a great deal of attention to the question of whether

African Americans should have the right to vote. In 1857, the state decided to

bring the issue before the public again as a referendum item in a gubernatorial

election of William Randall. They won the right to vote but it was contested by

citizens in the Western part of the state in court because they saw the right

to vote as a path to citizenship, which they opposed. After the Civil War,

African Americans began asking when they would get the rights they were entitled

to. The issue of voting was not just about giving African Americans the right

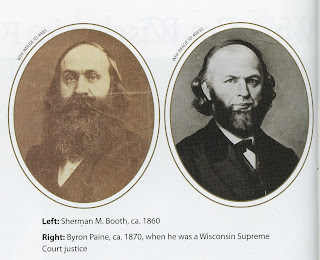

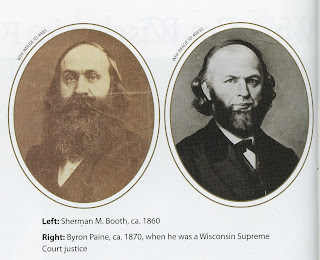

to vote, but rather empowering them to become equal citizens. After Ezekiel

Gillespie, a well-known Milwaukee entrepreneur had a dispute in a barbershop

regarding African Americans’ right to vote, he enlisted the help of Sherman

Booth and Attorney Byron Paine to petition the court on the matter. The court

reviewed the issue and found that it was no more than a mathematical error; the

totaling of the votes showed that they had the right to vote dating back to the

first referendum ballot in 1849. For more than 100 years no one took the

liberty to explain why there were miscalculations of the vote dating back to

1849.

In 2020, Wisconsin,

along with the nation is celebrating the 100th anniversary of

women’s suffrage. It’s clear that the right

to vote brings about citizenship, equality and empowerment, while at the same

time African Americans continue to be disenfranchised through voter

suppression, photo ID requirements, closing polls in the African American

community to control election outcomes and refusing to reinstate voting rights

to individuals previously incarcerated.