Guest post by Maddi Brenner

The First of Many Zoos

The public zoo we know of today began as far back as the 18th century when Europeans believed in obtaining new avenues of knowledge and developing their role in science, reason and logic. The first zoo, then known as a zoological garden or park, was created in Paris, France in 1793 and continued its expansion to other nations in Europe.[1] Historically, zoos emerged from several individuals involved in the hunting, trading, capturing, exhibiting and breeding of animals.[2] A prominent example and figure that “older generations of Americans might remember” was Carl Hagenbeck.[3] According to Nigel Rothfels, Hagenbeck revolutionized zoo design, its commercial business and the fundamental practices of zoos.[4]

A Pioneer of Zoo Curation and Practices

Born in 1844 in Hamburg, Germany, Carl Hagenbeck was a German merchant of wild animals and grew up alongside his father, Carl Hagenbeck Sr., as a fishmonger. As he grew older and increasingly interested in animals and the world, Hagenbeck began his travels to other countries, including but not limited to Egypt, Polynesia, Norway, Sweden and Finland. Around 1875, Hagenbeck traded his first “exotic” animals to zoos across Europe and the United States, where he combined his interest in commercial business and his love for showcasing to local folk. Carl Hagenbeck was so successful in his pursuit of animals and business that he used his skills to plan his own permanent zoo exhibit, then named the Park at Stellingen in Hamburg, Germany.[5] Daily, Hagenbeck journaled various methods and practices regarding the capturing and training of animals at the zoo. Highlights included animal trade, animal captivity and hunting, training wild animals and breeding. The first printing occurred in 1909, was named Beasts and Men: Being Carl Hagenbeck’s Experiences for Half a Century Among Wild Animals, with additional narratives and re-prints continuing until around 1912. Today, the book is still available and now translated into English and various other languages.[6]

|

| source: https://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=record_ID=siris_arc_399471&repo=DPLA |

Arguably, Hagenbeck was one of the most

famous European leaders in zoo development. P. Chalmers Mitchell, secretary of

the Zoological Society of London, reported Carl Hagenbeck as a prestigious figure

with candor and stamina for animal trade and the zoo business. He described Hagenbeck

as a “lover of animals and the greatest trainer” he’d ever seen.[7] His

success and fame were so iconic that many animal traders and zoo directors

across the world utilized his techniques. His popularity became known as the Hagenbeck

Revolution, where his work resembled that “of a showman more than of a

naturalist.”[8]

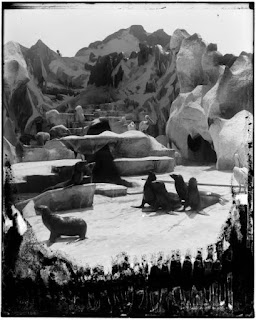

In his memoir, Hagenbeck portrays his relationship with animals as one of

curiosity and patience. He mentions his laborious training of sea lions and bears,

along with his firm belief that animals held in captivity needed care and sanctuary.

However, whether those feelings were for the actual good and nurturing of the animals,

or due to his imperative need for breeding and animal trade to ensure business growth,

is certainly up for debate.[9]

|

| Source: https://vintagraph.com/products/carl-hagenbecks-tierpark-stellingen?variant=12462662877286 |

The opening of the Park of Stellingen, today known as Tierpark Hagenbeck enabled Hagenbeck to explore various visual elements for animal exhibits. Most familiar and common today was a Panorama exhibit, which included barless habitats and revealed the animal in its more natural state using similar visuals of what one would see in the wild. These exhibits also gave zoos the opportunity to house many different animals in the same vicinity. With a moat that surrounded the landscape, animals could be viewed more easily (without bars). As Rothfels notes, these exhibits pointed to an illusion that allowed a visitor to idealize the world within the zoo itself.[10] Hagenbeck “wanted to create an animal paradise which would show animals from all lands and climatological zones in a manner suitable to their life conditions, not from behind bars and fences.”[11] His concepts and unique variety revolutionized the practice of zoo design and made him known as the inventor of the modern-day park. Tierpark Hagenbeck is still open today and has remained part of the Hagenbeck family business for more than 110 years. It is managed by the sixth generation of the Hagenbeck lineage and holds over 1,800 animals with 200 different species.[12]

|

| source: https://cdm17210.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/lpe/id/3389 |

Human Zoos and the Legacy of Hagenbeck

Hagenbeck considered himself an “ethnographic

showman” who believed that humans, typically of African and Asian descent were also

valuable for show. Hagenbeck presented people from various foreign countries to

a European audience, including “Sami, Nubians, Inuits, Somalis, East Indians

and other representatives of distant countries had to stage their everyday life

and their cultures.”[13] In

his memoir, Beasts and Men, Hagenbeck writes to his experience of ethnographic

exhibitions as a lucrative enterprise that he believed would “indubitably cause

a great sensation.”[14] Similarly,

he corresponds, “I bethought me of the Eskimos, those dwellers in the Artic of

whom we had all heard so much connection with polar expeditions, but who had

never yet been seen in the heart of Europe. It might be possible, I thought, to

bring a small party of these people to Hamburg.”[15]

Hagenbeck believed with a purpose that his role in showcasing humans was righteous and just. He imagined he had a responsibility to organize “frequent ethnographic exhibitions,” and wrote in his memoir, “one of the largest of all my ethnographic exhibitions was the great Cingalese exhibition of 1894. This great caravan, which consisted of sixty-seven persons with twenty-five elephants and a multitude of cattle of various breeds, caused a great sensation in Europe. I travelled about with this show all over Germany and Austria and made a very good thing out of it.”[16] With success of these shows across Europe, Hagenbeck believed these shows formulated and enriched “new forms of entertainment that fostered a revolution in the methods of training wild beasts for the zoo.”[17]

Those on display were working performers with tight schedules and little pay. Having been convinced to move from their home, these individuals and/or families often experienced traumatic, tiring and poor working conditions. For instance, “in 1880... an Inuit family on display died of smallpox because they had not been vaccinated. A group of Sioux Indians also died, of consumption, measles and pneumonia.”[18] Similarly, the parents of Theodor Wonja Michael traveled across Europe in exhibition as performers, after his father realized there weren’t many jobs being offered to a German of Cameroonian descent.[19] Michael recounts the experiences of his father, while speaking about his own experiences dancing and performing for an audience. He explains that the exhibits portrayed these cultures as “Africans: uneducated, bast-skirted and cultureless savages.” In a recent interview, 94-year-old Theodor Wonja Michael remembers being sniffed and gawked at while on display, including his speaking of broken German and/or sign language.[20] After Carl Hagenbeck died in 1913, his sons, Heinrich and Lorenz took over the zoo and circus business, continuing the human exhibits. Their last show of humans was in 1931, about 6 years after Theodor Wonja Michael was born into working these exhibitions.

Hagenbeck’s influence on modern zoo design

was revolutionary. He remains one of the most famous leaders in zoo practices not

only in Europe, but across the world. Yet, his legacy does live on in more ways

than one. With recognition of his contribution to the success of zoos, awareness

of his exploitation and ignorance at the expense of marginalized communities must

also be. He used his privilege to perform incidents of power over people that

cannot and should not be ignored. Today, there is strong criticism of zoo

history and of Carl Hagenbeck, himself, who as a pioneer in zoo practices was

also characterized as a deeply ignorant individual that supported the actions

of bigotry. Much scholarship and recent contemporary articles shed light on Hagenbeck’s

relationship with animals and humans. For better or for worse, we can use the

historical narrative of Hagenbeck to acknowledge how we remember and understand

the role of his work at zoos and in representation of various cultures today.

Epilogue: A Reflection on Hagenbeck and the Milwaukee

County Zoo

At the Milwaukee County Zoo, habitat practices

and modern zoo design were likely inspired by Carl Hagenbeck. During the 1920s

and 30s, the Milwaukee County Zoo, then known as the Washington Park Zoo,

replicated Hagenbeck-style exhibits with barless habitats, moats and natural

views of the animals.[21] At

the time, it was Director Edward Bean who fully embraced the performance of

natural habitats in zoos and believed this type of display could enrich the

experience of zoo-goers and animals. In similar ways, Bean and Hagenbeck both utilized

showcase techniques that sought the enrichment of animals on display. Bean’s practices

involved similar variations to Hagenbeck and ultimately transformed the ways in

which the Milwaukee County Zoo is developed today.

Reference

Hagenbeck, Carl. Beasts and Men, Being

Carl Hagenbeck's Experiences for Half a Century among Wild Animals. London:

Longmans, Green, and Co., 1912.

Reucher, Gaby. “A Life against Racism: Theodor Wonja

Michael.” DW.com. October 22, 2019:

https://www.dw.com/en/a-life-against-racism-theodor-wonja-michael/a-50935425.

Rothfels, Nigel. Savages and Beasts: The

Birth of the Modern Zoo. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Theodor, Michael and Eve Rosenhaft. Black

German: An Afro-German Life in the Twentieth Century. Liverpool: Liverpool

University Press. 2017.

Zeitler,

Anika and Rayna Breuer. “Carl Hagenbeck: The Inventor of the Modern Animal Park.”

DW.com. November 6, 2019: https://www.dw.com/en/carl-hagenbeck-the-inventor-of-the-modern-animal-park/a-49106027.

“Zoological

Garden.” Encyclopedia.com. May 21, 2018: https://www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/zoology-and-veterinary-medicine/zoology-general/zoological-garden.

[1]

“Zoological garden,” Encyclopedia.com, May 21, 2018: https://www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/zoology-and-veterinary-medicine/zoology-general/zoological-garden.

[2]

Nigel Rothfels, Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo,

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002, 8.

[3] Rothfels,

Savages and Beasts, 8.

[4] Rothfels,

Savages and Beasts, 8-11.

[5] Carl Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men: Being Carl Hagenbeck's

Experiences for Half a Century among Wild Animals, (London: Longmans,

Green, and Co., 1912); see image of front entrance to Stellingen Park from

Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men.

[6] Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men.

[7] Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men, x.

[8] Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men, viii-ix.

[9] Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men, 118-219.

[10] Rothfels,

Savages and Beasts, 42-44.

[11] Rothfels,

Savages and Beasts, 42-44.

[12]

Tierpark Berlin, https://www.tierpark-berlin.de/en/.

[13] Annika

Zeitler & Rayna Breuer. “Carl Hagenbeck: The Inventor of the Modern Animal

Park.” DW.com. November 6, 2019: https://www.dw.com/en/carl-hagenbeck-the-inventor-of-the-modern-animal-park/a-49106027.

[14] Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men, 20.

[15] Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men, 20-24.

[16] Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men, 29.

[17] Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men, 30.

[18] Zeitler

et al., “Carl Hagenbeck.”

[19] Theodor Wonja

Michael was born in Germany in 1925 and considered a journalist and public

servant. He was also a notable speaker on living as an Afro-German and a

prisoner in Nazi forced labor camps during Nazi Germany. See Theodor

Michael and Eve Rosenhaft, Black German: An Afro-German Life in the

Twentieth Century (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2017).

[20] Gaby

Reucher, “A Life against Racism: Theodor Wonja Michael,” DW.com, October 22,

2019: https://www.dw.com/en/a-life-against-racism-theodor-wonja-michael/a-50935425.

No comments:

Post a Comment